Dream job or empty fantasy? This is what it’s like to go horse trekking in the far north

Selena Anderson from Ahipara Horse Treks seems to have the perfect job. But what’s it like behind the scenes?

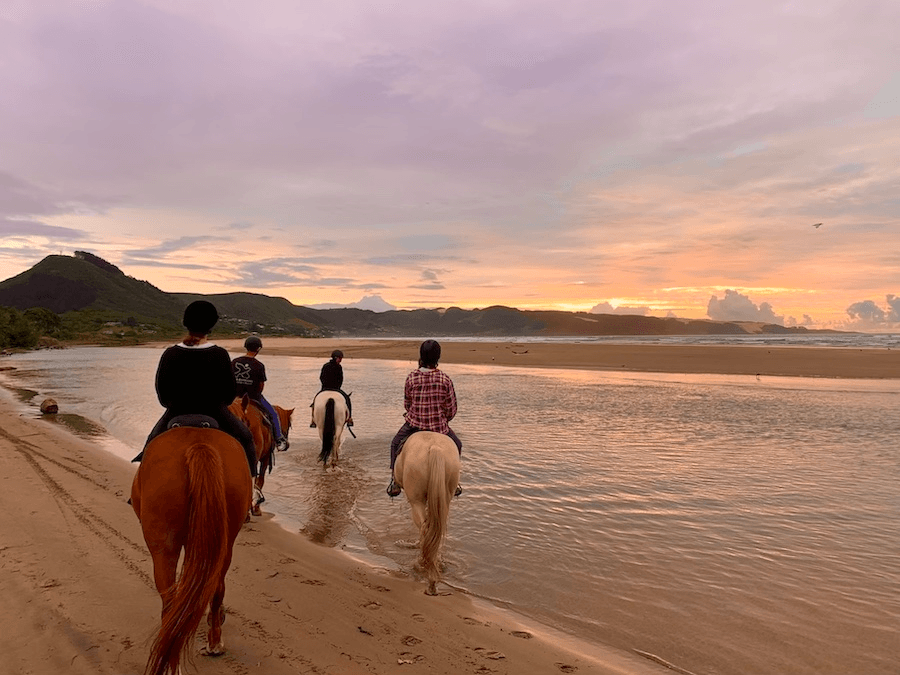

As I stand on my father’s terrace on the beach at Te-Oneroa-a-Tōhē (Ninety Mile Beach), I am met by a majestic sight. A solemn column of horses marches in step across the sand, backlit by the setting sun. The riders are bareback and serene. The procession loops from the sea’s edge to the mouth in front of my father’s house, the water’s surface rippling slightly with the pounding of hooves.

I should move hereI think this is the least horse-like creature a human can be. Become a riding instructor.

Selena Anderson, on the other hand, is more human than horse. She runs Ahipara Horse Treks and teaches horse riding full-time. How is your life? I ask myself this during the short car ride to the interview with her. It has to be… perfect?

“Having horses is tough,” says Anderson as I arrive at the trailhead on Foreshore Road in Ahipara. We are surrounded by chatty children and quiet ponies eating grass. “It’s tough in winter – you’re outside and you have to feed despite the rain and mud. The animal always comes first.”

My dream life has barely been scratched, but I push her to list more disadvantages. “With horses, there are always obstacles,” she continues. “You can get hurt – there’s always something.” She has to contend with strict health and safety regulations, horrendous vet bills and clients who have dangerously inflated ideas about their own riding skills.

Then the kicker: “You can’t make money with horses,” says Anderson with an ironic smile. “You won’t get rich with them.”

Money or no money, Anderson’s career was practically predetermined. A budding entrepreneur growing up on Waiheke Island, she offered pony rides on the beach in exchange for money for fish and chips. She attended a riding academy in her final two years of high school before spending three months teaching and riding in the US. It was on a ride through Aotearoa that she met her partner.

Since 2019, she has lived with him in Ahipara, leading beach walks and teaching people – mainly children, up to 30 per week – how to ride.

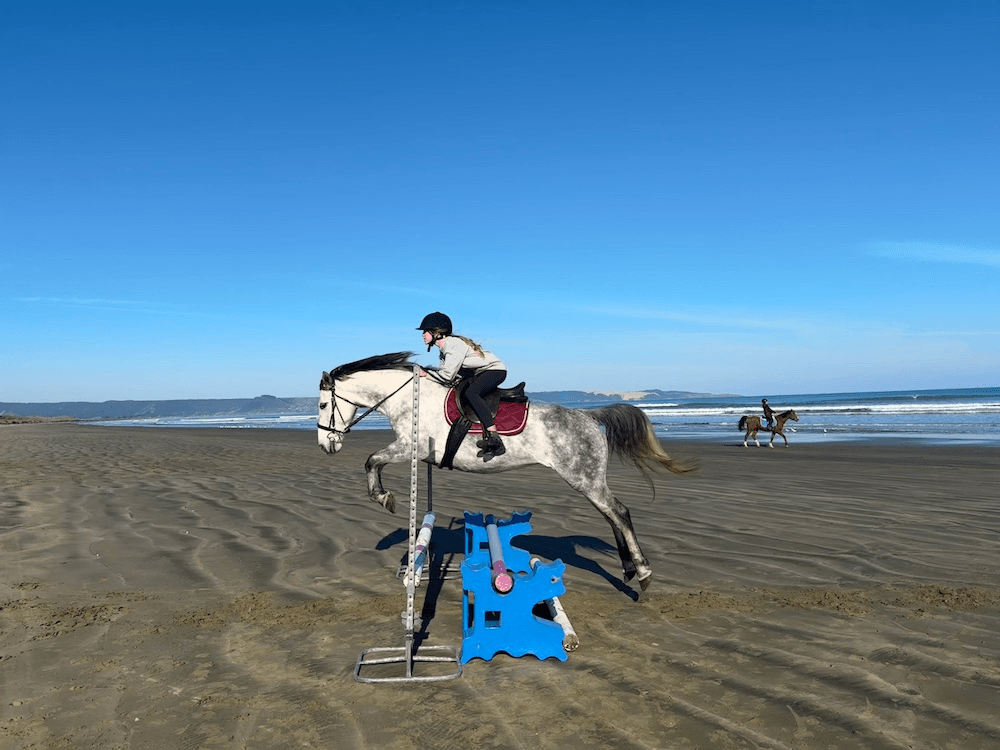

Most children start as absolute beginners, and Anderson has them bareback and showjumping within a couple of years. Her youngest student is five. The horses have to be bombproof, Anderson says: On the beach, they have to cope with parents pushing strollers, dogs off leash, kites, blokarts and – the most nerve-wracking of all – motorcyclists who “show off” by doing doughnuts around the horses.

The resilience of Anderson’s 29 horses is all the more remarkable when you consider that most of them wild animals she has collapsed into herself. The secret? “Time,” says Anderson, “and getting used to everything.”

I ask what the best part of the job is. I can already imagine my own answer: the seaside scenes, the peace and quiet, the complete escape from the rat race. No boss, no drivers from Auckland, no passive-aggressive email closings.

“Horses,” she replies.

I’m surprised when Anderson tells me that she sometimes longs for a life like mine. “Sometimes, when it’s super hot or the weather is bad,” she says, “I wish I had an office job.”

Ahhhhh, the old “the grass is greener” trick. It gets us every time. After 20 minutes of chatting with Anderson, the ponies neighing around us, I know she wouldn’t last a day at the office. It’s clear that her fleeting fantasy of trading horses for email is as useless as my own daydream. I couldn’t put on a bridle if a gun was held to my head.

I think about the fickle nature of desire, while Anderson thinks about the Trek for lifeanother horse activity she organizes (Trek for Life is an annual week-long horse trek through remote regions of New Zealand to raise money for first aid and rescue services). When Anderson pauses, I ask her what she does in her free time. The answer hangs in the air for a split second, so obvious that we both start giggling.

“Guess what,” she says with cheerful irony. “I’m going horseback riding.”