Incarcerated fathers and daughters reunite for a dance in Netflix documentary | Richmond Free Press

Angela Patton has dedicated her career to the needs of young girls. Over a decade ago, the CEO of the nonprofit Girls For a Change and founder of Camp Diva Leadership Academy helped launch a program in Richmond that created a father-daughter dance for girls whose fathers are in prison. But the idea for “Date With Dad” didn’t come from her. It came from a 12-year-old black girl.

The popularity of a TEDWomen talk about the initiative in 2012, which was viewed over a million times, prompted many filmmakers to be eager to tell the story. But she felt no one was right until Natalie Rae came along.

“Natalie actually made the effort and put in the energy to visit me, get to know the families I’ve worked with in the past, and just learn and be a willing participant,” Patton told The Associated Press during the Sundance Film Festival in January.

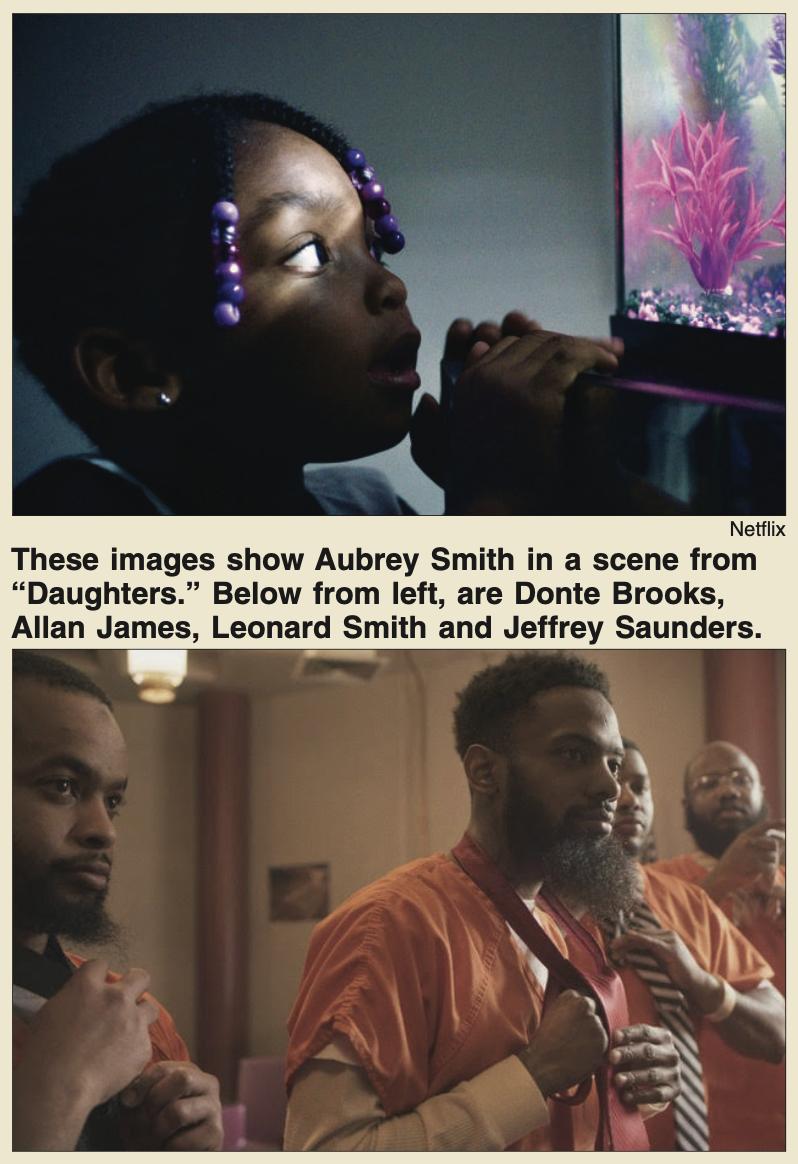

The two began their eight-year journey as co-directors to create the documentary “Daughters,” which follows four young girls as they prepare to reunite with their fathers for a dance at a Washington, D.C. prison. The Sundance Award-winning film, executive produced by Kerry Washington, is available on Netflix this week.

Featuring intimate moments in the girls’ homes and glimpses into the intensive 12-week therapy session their fathers previously attended, Daughters paints a moving and complex portrait of broken bonds and their healing.

“It was just one of the most powerful stories I’ve ever heard,” Rae said. “For me, it was a beautiful example of the changes that can happen in the world when we listen to the wisdom of young women.”

This is a young black girl’s idea and she knew what she and her father needed.”

With this in mind, the two filmmakers agreed that they wanted to shoot “Daughters” from the girls’ perspective.

“I’m always advocating for them,” Patton said. “I hear them say, ‘I care about my dad, but I’m really mad at him right now.’ Or ‘My dad is great, and someone else is trying to tell me he’s not, and I want you to not see my dad as the bad guy because he made a bad decision. But he still loves me.’ I hear all of these experiences from a lot of girls in the community. I want to see how we can help them.”

Although Patton has worked with black families in Washington and Richmond for many years, the film required a new level of trust by building close relationships with the girls and their mothers, asking them what they needed and were comfortable with, and knowing when to turn the cameras on and off.

“You have to get to know the families. I am convinced that we can only build trust in the community if we achieve something together with them,”

Patton said, “I’ve been doing this for over 20 years. I’ve built up a certain reputation. … They call me Sister Angela. You know, ‘She’s got our backs. She’ll protect us.'”

Rae was new to this world, but Patton said her co-director “took it to the next level” by getting to know her subjects and gaining their trust.

“These are truly lifelong relationships,” Rae said. “Most of the time we’re not filming. We spend time visiting someone in the hospital or going to a birthday party.”

“Aubrey (one of the characters) and I once made a birthday cake for her father and were able to talk to him on the phone and just tell him what it looked like.”

Daughters is a film that some people call a “three-handkerchiefs” movie that is sure to tug at the heartstrings. The filmmakers hope it can also lead to change, a powerful example of the importance of visits where girls can hug their fathers.

“We really want to show the impact this system and incarcerated fathers have on families and daughters, and raise awareness about the importance of touch visits and family bonding,” Rae said.

In a joint statement from the two directors, provided to Netflix, they explain what kind of story “Daughters” tells.

“This is not a sad story. This is a love story,” the directors emphasized. “It is a healing story about how those who experience the worst of our country’s broken systems often have the best ideas about how to remain human inside until revolution comes.”

Richmond Free Press writer Paula Phounsavath contributed to this report.