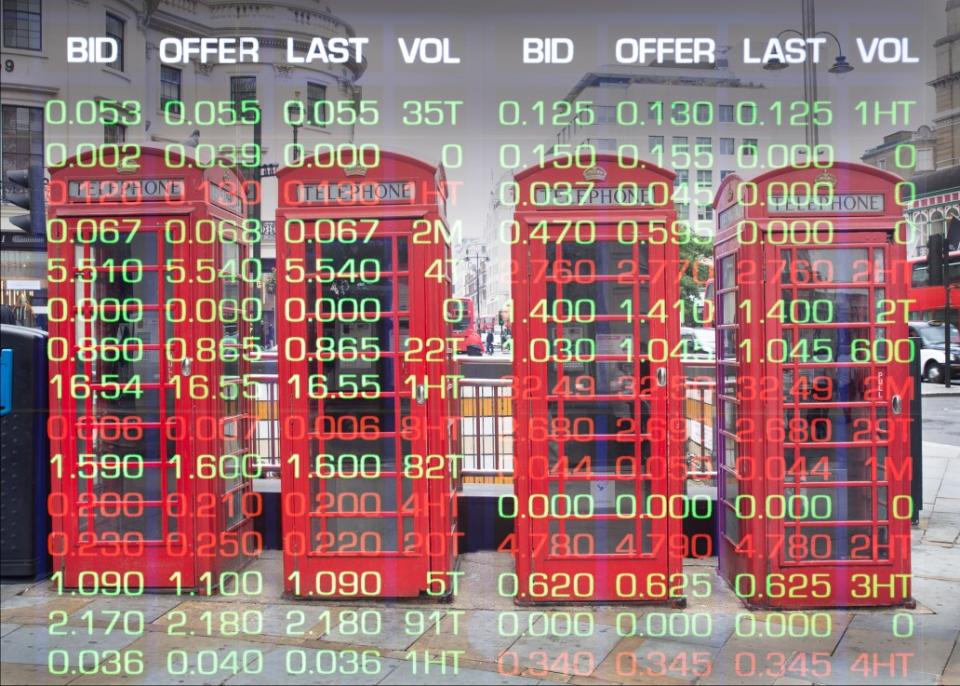

Only quick solutions can save the London Stock Exchange from an exodus in 2024

The London Stock Exchange has suffered serious injuries over the past two years. James Ashton, CEO of the Quoted Companies Alliance, is warning the Chancellor that now is the time to take action.

Just imagine if the FTSE 100 lost its three largest constituents. What if pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca, energy giant Shell and HSBC, one of the world’s largest lenders, decided to list their shares elsewhere? What if the trio left the London market within a year of each other?

Of course, while the mood is feverish as gaming group Flutter Entertainment prepares to move its main listing to New York, this is highly unlikely. In fact, it sounds like yet more miserabilism that the urgent issue of fixing London’s stock markets simply does not need. And yet, across the Irish Sea in Dublin, that very exodus is taking place.

Building materials group CRH ceased trading on Euronext Dublin last September, followed by the delisting of Flutter, whose brands include Paddy Power, last month. Packaging group Smurfit Kappa will also leave the market once its merger with US rival WestRock is approved. Together, these three companies accounted for more than half of all share trading in Dublin.

A repeat of the Irish crisis would require many more departures from London. But the collapse of Dublin’s stock market, which resembles Ernest Hemingway’s two kinds of bankruptcy – first gradual, then sudden – should put British politicians and financial regulators on high alert.

There are many differences between the London and Dublin stock exchanges – their size and liquidity, to begin with. But there are also similarities: the pull of New York, the loss of the home bias that meant companies naturally traded their shares close to their headquarters, and the recent lack of IPOs.

And London has significantly more to lose than Ireland. In the last two months alone, the city has lost an alarming 35 public companies, more than Dublin has in its entire ecosystem.

That’s why the Quoted Companies Alliance is calling for a series of quick fixes in the 6 March Budget to give new impetus to the ongoing work to future-proof London’s stock markets. Crucially, what is often seen as a top-down problem – how to prevent flagship British companies being lost to overseas markets – requires some bottom-up solutions. If we nurture our small and midcaps – those operating in advanced industries such as fintech, biotech and digital media, and driving regional economic growth – they will have the best chance of becoming the blue chips of tomorrow.

We are calling for the abolition of stamp duty on share dealings for companies outside the FTSE 100. Such action is one of the strongest signals the Chancellor of the Exchequer can send of the Government’s commitment to our public markets in the heart of the City of London. At a cost of no more than £650 million a year, this move would attract investor interest in hundreds of domestic companies and strengthen the UK’s competitiveness with the US and Germany, where there is no comparable transaction tax.

If we don’t invest a large proportion of our considerable assets in Britain’s remarkable entrepreneurial prospects, why should anyone else?

It’s also time to overhaul the ISA system. Convert ISAs to UK ISAs (BRISAs), so that in future every pound invested in shares of foreign companies is matched by at least one pound in UK shares. Retail investors could still put Apple or Tesla shares in their BRISAs, but a direct link must be restored between the generous tax relief these products offer and the support of the UK companies that grow and invest here.

To thrive, the UK needs to play to its strengths. And one of those is our huge asset management industry, which Ireland and almost every other country cannot compete with. How can more of that money be put to productive use right on the doorstep of these funds? British pension funds, which receive billions of pounds of taxpayers’ money, should explain why they invest far less in domestic equities than many other foreign pension funds manage to deploy capital in their own market.

Exit door of the London Stock Exchange swings open

This should start with a simple, clearly visible figure, the percentage of assets invested in UK equities, so that a fund’s clients, politicians and the media can compare and make informed decisions. It would be similar to the single-digit remuneration that companies have to disclose to show how much their chief executive takes home.

One institution that can do better is Nest, Britain’s largest defined contribution occupational pension scheme. Every month it receives £500 million in new contributions, largely from low- to middle-income earners, but only a fraction of that is invested in Britain, in the businesses of those working-class communities that are providing the goods, services and jobs of the future. There is nothing fundamentally wrong with betting on the US artificial intelligence leader Nvidia to make huge profits today, but what about the homegrown companies that will underpin the UK economy tomorrow? There should be a much better match here.

Another organisation we would like to see is the British Business Bank. This week I am writing to Business Secretary Kevin Hollinrake asking him to reconsider its remit. Supporting venture capital companies is commendable, but growth companies are also public and the British Development Bank needs to do a better job of recognising this.

Similarly, too little of the £50 billion of pension fund capital raised last year through the Mansion House Compact is reaching the AIM and Aquis Growth Market stocks that were part of the original plan.

If we want our public markets to thrive while others languish, we need to put capital where it is needed most: in high-growth stocks. Because if we don’t put some of our considerable assets into Britain’s remarkable entrepreneurial prospects, why should anyone else?