The rising costs of decommissioning offshore oil and gas fields

By Andrew Burr, North America Analyst, Welligence Energy Analytics

(First registration) The safe, timely and cost-effective decommissioning of offshore infrastructure is one of the major challenges facing the oil and gas industry.

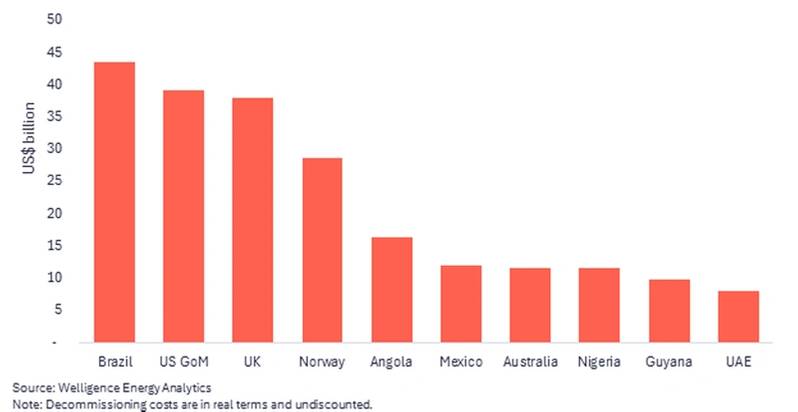

We estimate that liabilities currently stand at over $300 billion (in real terms), and this figure will only rise as companies continue to discover and develop new oil fields. The largest offshore producers, Brazil, the Gulf of Mexico, the UK and Norway, have the highest bills to pay, totaling nearly $150 billion.

Global offshore decommissioning – Estimated costs by country

A key concern for governments is to ensure that the sector is able to meet these decommissioning obligations and that the costs are not borne by the taxpayer. Several high-profile offshore bankruptcies in recent years have exposed regulatory weaknesses that put taxpayers on the hook. Countries are working to tighten their rules, most recently in the US, where the Board of Oil and Gas (BOEM) introduced new rules for the US Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) that brought the issue into focus.

Immerse yourself in the landscape of abandonment in the US GoM

The U.S. Governor of Mexico is one of the hardest hit areas, accounting for nearly $40 billion of the global costs – around 80% of which are attributable to deepwater projects. The largest cost is the decommissioning of subsea wells. While most of the equipment can be washed away and sold as scrap, the wells must be worked on site and require the use of vessels to plug and decommission the well. According to reports to BOEM, these costs average $28 million per well.

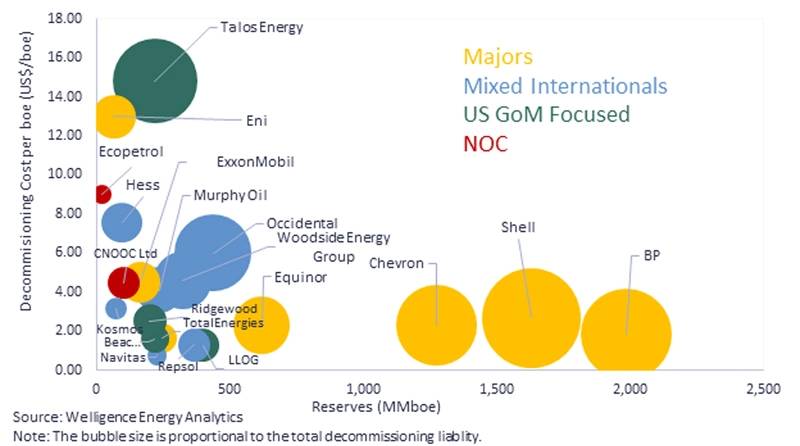

According to the regulator, there are nearly 100 companies in the U.S. federal budget with some type of liability. The majority of the liability (about 70%) is associated with the 15 largest E&P companies, all of which are large companies with large balance sheets and major participants in deepwater projects. The three major traditional producers (BP, Chevron, Shell) are the most affected, as well as Talos Energy due to the large infrastructure-based portfolio the company has built up in recent years through its M&A strategy.

Corporate liability for deep-sea basin closures – most at risk

Taxpayer protection – chain of ownership and guarantees

Governments are enacting regulations to ensure that liability for shutdowns does not fall on taxpayers. Some cases underscore this concern. In Australia and New Zealand, recent bankruptcies of E&P companies resulted in taxpayers being saddled with costs of $215 million and $192 million, respectively. In fact, the U.S. Department of the Interior states that the new regulations for the U.S. OCS “…will protect taxpayers from incurring costs that should be borne by the oil and gas industry when offshore platforms have to be shut down.”

- Ownership chain: Countries enact regulations to ensure that companies cannot simply “sell” their decommissioning obligations and forget about them – in the event of bankruptcy, the transferred liabilities can revert to the original sellers through the historical chain of ownership. While establishing this chain can be very difficult in the U.S., it is much easier offshore because the parties involved are usually established companies.

When Fieldwood went bust in the US Governor’s Palace, it was left with $2.5 billion in decommissioning obligations. These were passed on to the previous owners of the plants, with Apache, BP, Marathon Oil, Shell and Chevron being hit hardest. This was not only an unwelcome financial surprise, but also a major operational challenge, as most had not been involved in projects for over 10 years. - Financial collateral: Although these companies have met their obligations, BOEM has nevertheless been forced to further tighten its regulations for the U.S. OCS. The new rules require additional financial collateral to cover the decommissioning costs of companies that do not meet the new financial strength criteria. The large players are largely unaffected, but there is a long list of smaller companies that will struggle to meet the new criteria and will therefore bear the brunt of the increased financial collateral costs.

The new rules have faced significant opposition from industry, which argues they will impact investment and business deals. But such rules should come as no surprise – the US is now in line with Brazil, the UK and Norway, all of which have introduced similar regulations in recent years.