Senegalese girls can become wrestlers – and win. But only until they get married

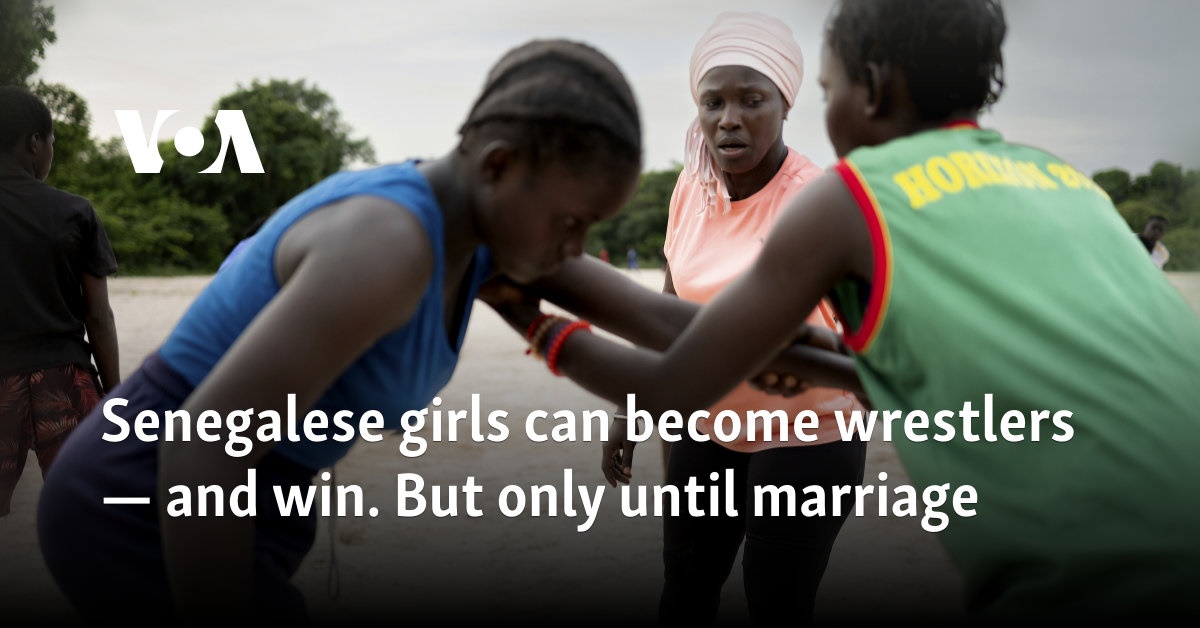

It is almost dark, the West African heat is finally easing. In Mlomp, a village in southern Senegal, dozens of young people in colorful jerseys are throwing themselves to the ground to the rhythm of Afrobeats in front of a backdrop of palm trees.

It’s a common sight across Senegal, where wrestling is a national sport and wrestlers are celebrated like rock stars. The local version of wrestling, called laamb in Wolof, one of the national languages, has been part of village life for centuries. Senegalese wrestle for entertainment and to celebrate special occasions. The professional version of the sport draws thousands to stadiums and can be a catapult to international fame.

But in most parts of the country, wrestling is still taboo for women.

There is one exception. In the Casamance region, home to the Jola ethnic group, women traditionally wrestle alongside men. At a recent training session in Mlomp, most of the young people on the sand were girls.

“It’s in our blood,” says coach Isabelle Sambou, 43, a two-time Olympian and nine-time African wrestling champion. “In our village, girls wrestle. My mother was a wrestler, my aunts were wrestlers.”

However, when Jola women marry, they are expected to give up their religious practices and devote themselves entirely to family life, which is considered the primary duty of Senegalese women regardless of their ethnicity or religion.

Sambo’s aunt, Awa Sy, now in her 80s, was the village mistress in her youth and said she would even defeat some men.

“I liked wrestling because it made me feel strong,” she said in front of her house, which is located between rice fields and mangroves. “When I got married, I stopped doing it.” At the time, she didn’t question it.

This was not the case with her niece, who, despite her humble nature and small size, exudes strength and determination. She overcame many obstacles to become a professional athlete.

As a teenager, Sambou was discovered by a professional wrestling coach during a competition at the annual King of Oussouye Festival, one of the few events open to women. The coach suggested she try Olympic wrestling, which has a national women’s team, but she only agreed after her older brother convinced her.

Sambou, who did not finish primary school, was able to compete in wrestling at the Olympic Games in London and Rio de Janeiro, where she did not finish in the medal ranks. But being a successful professional athlete in a conservative society comes at a price.

“When you’re a female wrestler, people make fun of you,” says Sambou, recalling her experiences in parts of Senegal outside her home region. “When I was walking around in shorts, people would say, ‘Look, is that a woman or a boy?'”

Others claimed that her body was changing and she would no longer look like a woman.

Such things can go to your head, says Sambou. “But I tell myself: They don’t know what they’re talking about. It’s in my blood and it’s brought me to where I am today.”

In 2016, in her mid-30s, she decided to retire from professional sport and return to her village.

“I thought it was time to stop and think about something else, maybe get a job, start a family,” she said. “But that hasn’t happened yet.”

Instead, she focused on finding “future Isabelles.” After her dream of winning an Olympic medal fell through, she now hopes that a girl she coaches can achieve that.

This mission is complicated by a lack of resources. Women’s sport is often underfunded, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

In Sambou’s village, there are no gyms where the girls can do weight training. They don’t have the special shoes used in Olympic wrestling, so they train barefoot. They don’t have mats, so they have to make do with sand.

And yet, Sambou’s students won ten medals, including six gold medals, at the African Youth Wrestling Championships held in Senegal’s capital, Dakar, in June.

“Despite everything, they did a great job,” she said.

She has received little for this. In Senegal, there is no pension system for former professional athletes. Her lack of formal education makes her career as a coach difficult. She helps coach the national wrestling team, both men’s and women’s, but on a voluntary basis. To make ends meet, she works in a small shop and cleans people’s houses.

“I gave everything for wrestling and for my country,” she said. “Now I have nothing. I don’t even have my own house. That hurts a little.”

She listed the countries she has visited, including the United States and Switzerland, while sitting outside her home, which she shares with relatives. Her bedroom is decorated with an image of the Virgin Mary and posters celebrating her participation in championships – the only sign of her glorious past.

“It’s difficult being a professional athlete. You have to leave everything behind,” she said. “And then you stop, come back here and sit here with nothing to do.”

But times are changing and so is the perception of women in Senegalese society. Today, parents turn to Sambou and ask her to train their children, regardless of their gender, even though it is still free.

Sambou’s 17-year-old niece, Mame Marie Sambou, recently won a gold medal at the youth championships in Dakar. Her dream is to become a professional wrestler and compete internationally. The big challenge comes in two years when Senegal hosts the Youth Olympic Games, the first-ever Olympic event on African soil.

“My aunt encouraged me to start wrestling,” she said. “When I started, a lot of people said they had never seen a girl wrestle. But I never listened to them. I want to be like them.”