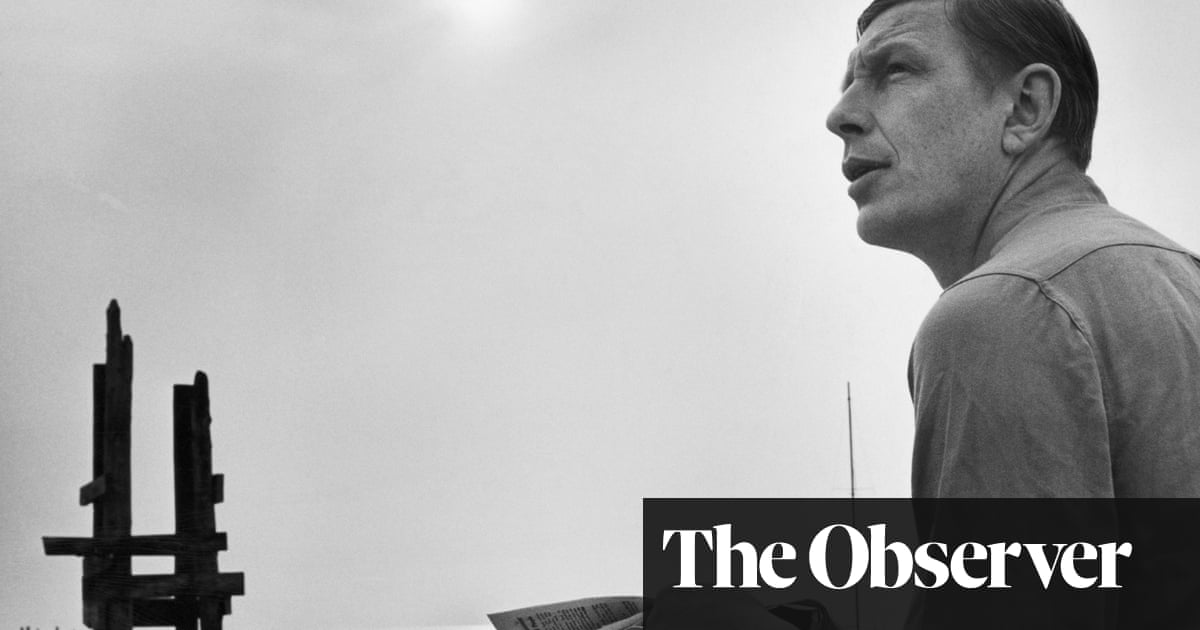

The Island: Review of WH Auden and the Last of Englishness – a deep insight into the poet’s early years | WH Auden

T25 years ago, my father and I were hiking in the Peak District. Beside us was his dog; before us lay a familiar mountain, low, craggy and bare. My father was boasting, as he often did, about the cairn at the top of the mountain, a cairn he claimed to have created himself, when suddenly, out of nowhere, the silhouette of a man appeared next to it: first a head, then a torso, and finally a pair of legs. “Ah,” said my father, so wisely that it startled me. “A caver.” We stood there, blinking. Moments later, another man materialized, and then another: a human string of sausages, pulled as if from a cylinder from the darkest depths of the limestone.

The memory of this came to me while reading The Island: WH Auden and the Last Remnant of Englishnessa new study of the poet and his world. In part, this was because Auden had visited the same mountains as a schoolboy; even before he became fascinated by the abandoned lead mines of the northern Pennines, he had seen – in 1919, when he was 12 – the Blue John Cavern near Castleton in Derbyshire, a place he would later describe as one of the names on his “numinous map” of sacred places. But above all, it was because cave exploration is a good metaphor for the experience of reading Nicholas Jenkins’ book, which runs to 543 pages (minus the extensive notes). Headlights readyI thought every time I opened it.

There are beautiful moments along the way. After hours (or days!) of squeezing through narrow corridors – a close reading of a single poem can stretch to 10 pages – an unexpected vista finally opens before you: the kind of vista that makes you dig through tattered paperbacks for more. But such revelations are hard to come by. Jenkins, who teaches at Stanford University, is only interested in the first 30 years of Auden’s life – the book ends in 1937, just before the poet’s departure for New York – and even here he is selective; his focus on ideas of Englishness means that Auden’s experiences in the Spanish Civil War, among other events from the period, are given scant attention. Ultimately, this is not a volume for the general reader, and perhaps not even for the Auden fan. If I am glad to have read it myself, it is for somewhat sad reasons. Given the painful decline of English university literature, such scholarship (and verbosity) seems to me like a last gasp. Will people still be writing such books in 50 or even 10 years? It’s hard to imagine.

The islandis very biographical, but not a biography; the book it most resembles in my opinion is Peter Parker’s Housman Country: Into the heart of England, a study of AE Housman (though Parker’s instincts – I mean this as a compliment – are more folksy than Jenkins’). Broadly speaking, it is about the many things that influenced the young Auden and fed into his poetry; Jenkins digs into the verse like a miner, bringing each influence to the surface (again, I imagine a crack in a hill). The First World War is, of course, ever-present: as powerfully black for Auden as “the vast bat shadow of home”, even if his generation did not fight against it.

after newsletter campaign

But there are other mainstays too: family, school and sex; modernism (Tom Driberg introduced him to TS Eliot at Oxford) and Freud (Auden’s father, Birmingham’s first school doctor, was an early adopter of psychoanalytic techniques). The result is, at its best, a richly textured landscape, not only in its complexity of mood but also in its cast of strange, colorful and sometimes highly dubious characters (though Jenkins is right to oppose censorship). It is surprisingly exciting to imagine Auden reading The Wonderful World of Love to JRR Tolkien. Beowulf (he didn’t understand any of it, but knew immediately that it was “his thing”) – and it was pretty grim to read of Geoffrey Hoyland, the headmaster of Downs, a school in the Malvern Mountains where Auden was employed in the mid-1930s, wandering around a hall of residence at night stark naked and with a full erection. Some readers will take issue with Jenkins’s claim that Auden was “genuinely in love” with Michael Yates, a 13-year-old pupil.

The most daring chapter is devoted to the poet’s time in Weimar-era Berlin, a city then home to 35,000 male prostitutes. Auden gets it on with a “stout sailor” called Gerhart Meyer, though Jenkins is more interested in the symbolism of such encounters – these “meetings” with Germans were acts of peacemaking, he instructs, and we shouldn’t get too hung up on Auden’s bruises – than in the fun of them; the sheer relief. But in truth I was more drawn to the earlier parts of the book, which deal with Auden’s obsession with the escarpments and industrial archaeology of the north – the landscape he would eventually extol in the great poem “In Praise of Limestone” (1948).

Most of the places Jenkins describes haunt me too – and although I have long known and understood the poet’s subterranean connections between the First World War (trenches), mining (shafts and tunnels) and his father (who served in the Royal Army Medical Corps), those connections definitely come alive here. It is a little miraculous to me that one of Auden’s most treasured handbooks during his childhood was called Lead and zinc ores from Northumberland and Alston Moorand next time I’m high, I might just take my old Selected poems in my backpack: “This cut-off country will not communicate…”